celestial harmonies

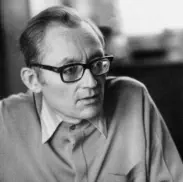

Jean Barraqué

17 January 1928 – 17 August 1973

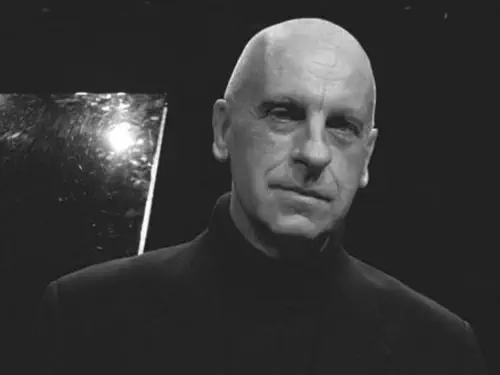

Roger Woodward

* 20 December 1942

In 1961 the French musician and author André Hodeir, best known as a jazz critic,

but also part of the Parisian circle of artists and intellectuals around the young

Pierre Boulez, published a book called Since Debussy. Its opinions (which largely

coincided with those of Boulez) are generally scathing. Of Stravinsky, he says: “it

would be almost indecent to mention him in the same breath with Debussy”, while

Schönberg “who remained an exceptional creator as he was busy destroying,

ceased to be truly creative as soon as he tried to construct”. Berg (though praised in

part) “wasted the last years of his life in a sterile attempt to retrace his steps”. He

refers to the “uncertainty and mediocrity” of Bartók’s last works, finds much to

admire in Messiaen, but also finds that “even his best pages lack that assertive

power which is the sign of the authentic masterpiece”.

So who survives this onslaught? Of the older composers, only the then relatively

obscure Anton Webern, who is being hailed—almost sanctified—by the young

avant-garde as the “Pioneer of a New Musical Order”. And of the young, just three

composers, all of whom just happened to have studied with Messiaen in Paris:

Pierre Boulez, Karlheinz Stockhausen, and Jean Barraqué. Stockhausen, though not

accorded a chapter of his own, is mentioned frequently with considerable respect.

Boulez is hailed (somewhat equivocally!) as “one of the greatest precursory figures

in Western art and thought, one of those men without whom things would not be

what they are”, yet ultimately, as a young Moses whose work gets stuck at the

border of the Promised Land: stuck not least through increasing caution, and an

excessive preoccupation with polish and style (coming in the immediate wake of Pli

selon pli, this is perhaps a rather prophetic comment).

All this would already have been enough to guarantee a degree of controversy, but

in the final major chapter Hodeir goes several steps further. Its subject, Jean

Barraqué, is virtually unknown outside the Boulez circle, and his acknowledged

output consists of just four works (he will complete only three more before his

death in 1973), of which only a couple of have been performed. But this doesn’t

prevent Hodeir from hailing him as even more important than Debussy (which also

implicitly raises him above Boulez). And the work on which he heaps the greatest

praise is one that has not yet been performed in public (and will not be until 1967),

a Piano Sonata (1950-2) that has recently been issued on Lp, in a quasi-performance

by Yvonne Loriod patched together in the studio from countless short ‘takes’, but

whose score would not be available for a few more years. He writes “one is amazed

to think that this towering score [is] the work of a very young man. Certain works of

Mozart and Schubert are astonishingly precocious; this one is terrifyingly so.” And

he concludes: “It is unclassifiable, incomparable, and to some degree, still

incommunicable music…this music lies outside the scope of our era, in any case; it

can only belong to the future.”

Jean Barraqué

Sonate pour piano

Roger Woodward

13325-2

p.o. box 30122

tucson, arizona 85751

+1 520 326 4400

+1 520 326 3333 fax

celestial@harmonies.com

In 1961 the French musician and author André Hodeir, best known as a jazz critic,

but also part of the Parisian circle of artists and intellectuals around the young

Pierre Boulez, published a book called Since Debussy. Its opinions (which largely

coincided with those of Boulez) are generally scathing. Of Stravinsky, he says: “it

would be almost indecent to mention him in the same breath with Debussy”, while

Schönberg “who remained an exceptional creator as he was busy destroying,

ceased to be truly creative as soon as he tried to construct”. Berg (though praised in

part) “wasted the last years of his life in a sterile attempt to retrace his steps”. He

refers to the “uncertainty and mediocrity” of Bartók’s last works, finds much to

admire in Messiaen, but also finds that “even his best pages lack that assertive

power which is the sign of the authentic masterpiece”.

So who survives this onslaught? Of the older composers, only the then relatively

obscure Anton Webern, who is being hailed—almost sanctified—by the young

avant-garde as the “Pioneer of a New Musical Order”. And of the young, just three

composers, all of whom just happened to have studied with Messiaen in Paris:

Pierre Boulez, Karlheinz Stockhausen, and Jean Barraqué. Stockhausen, though not

accorded a chapter of his own, is mentioned frequently with considerable respect.

Boulez is hailed (somewhat equivocally!) as “one of the greatest precursory figures

in Western art and thought, one of those men without whom things would not be

what they are”, yet ultimately, as a young Moses whose work gets stuck at the

border of the Promised Land: stuck not least through increasing caution, and an

excessive preoccupation with polish and style (coming in the immediate wake of Pli

selon pli, this is perhaps a rather prophetic comment).

All this would already have been enough to guarantee a degree of controversy, but

in the final major chapter Hodeir goes several steps further. Its subject, Jean

Barraqué, is virtually unknown outside the Boulez circle, and his acknowledged

output consists of just four works (he will complete only three more before his

death in 1973), of which only a couple of have been performed. But this doesn’t

prevent Hodeir from hailing him as even more important than Debussy (which also

implicitly raises him above Boulez). And the work on which he heaps the greatest

praise is one that has not yet been performed in public (and will not be until 1967),

a Piano Sonata (1950-2) that has recently been issued on Lp, in a quasi-performance

by Yvonne Loriod patched together in the studio from countless short ‘takes’, but

whose score would not be available for a few more years. He writes “one is amazed

to think that this towering score [is] the work of a very young man. Certain works of

Mozart and Schubert are astonishingly precocious; this one is terrifyingly so.” And

he concludes: “It is unclassifiable, incomparable, and to some degree, still

incommunicable music…this music lies outside the scope of our era, in any case; it

can only belong to the future.”

celestial harmonies

p.o. box 30122

tucson, arizona 85751

+1 520 326 4400

+1 520 326 3333 fax

celestial@harmonies.com

Jean Barraqué

17 January 1928 – 17 August 1973

Jean Barraqué

Sonate pour piano

Roger Woodward

13325-2

Roger Woodward

* 20 December 1942