celestial harmonies

p.o. box 30122 tucson, arizona 85751

+1 520 326 4400 fax +1 520 326 3333

celestial@harmonies.com

BL

ACK O SUN

Johannes Brahms

Piano Concerto № 1 d-minor op. 15 (1858)

Maestoso

Adagio

Rondo: Allegro non troppo

Sándor Falvai, pianist

Hungarian National Philharmonic Orchestra

Zoltán Kocsis, conductor

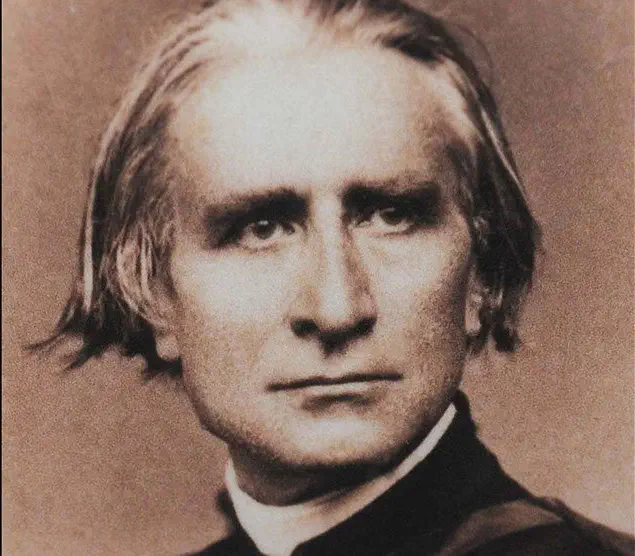

Franz Liszt

Trois odes funèbres S. 112 (1860-1866)

Les Morts – Oraison

La Notte

Le triomphe funèbre du Tasse

Hungarian National Philharmonic Orchestra

Zoltán Kocsis, conductor

Eine Eckart Rahn Produktion

Celestial Harmonies 14333-2

Recorded June 13-17, July 20, 2016 in Budapest

Photo: László Kenéz

On 23 August 1874 Franz Liszt wrote a letter to his former secretary, the

composer Peter Cornelius: “For a long time I’ve had a couple of manuscripts

finished that I would like to send to Schott for publication. Yet I fear that they will

lie about there unread. The very title, Three Symphonic Funeral Odes (Trois Odes

funèbres symphoniques) will probably frighten them off; moreover, the full scores,

each roughly twenty pages long, would have to appear simultaneously with the

piano transcriptions (for two or four hands).”

Liszt had sized up the situation correctly: of the Trois odes funèbres he

composed between 1860 and 1866, only the third, Le triomphe funèbre du Tasse,

was published during his lifetime both in full score and a piano version, albeit not

by Schott, but by Breitkopf & Härtel. Of the other two odes, Les morts and La

notte, he would only witness the publication of a piano version of La notte (Schott,

1883). It was not until three decades after his death that Les morts and the

orchestral version of La notte finally appeared in print.

One reason for the convoluted publication history of the Odes was probably

the fact that none of them fit easily into the image of an autonomous and self-

contained work of art. This is primarily due to the fact that each exists in several

conflicting versions. Not only does each of the three Odes have arrangements for

solo piano and piano duet in addition to its orchestral version, there is also an

organ version of Les morts, one for violin and piano of La notte, and a two-piano

arrangement (admittedly lost) of Le triomphe funèbre du Tasse. In several cases it

is almost impossible to tell what is temporary and what is definitive, or which is

the original and which the arrangement. Further, La notte is a paraphrase of an

earlier piano piece (Il Pensieroso from the Italian volume of the Années de

pèlerinage), and Le triomphe funèbre du Tasse is an epilogue to Liszt’s second

symphonic poem, Tasso: Lamento e trionfo. The latter Ode in particular is almost

unintelligible without a reference to the symphonic poem of several years earlier.

All the same, it is precisely this lack of independence, this need for a larger frame

of reference, that constitutes the unifying feature of the Three Odes. Each turns on

the central idea of recollection and reminiscence. In the second and third Odes the

reminiscence is purely musical: both recall an earlier composition. In the case of

Les morts, however, the reminiscence is extra-musical: it recalls not only the

deceased in general, but specifically Liszt’s son Daniel, who had died only a few

months before Liszt embarked on the composition.

Composed in 1860, Les morts is based on the like-named oraison (prayer) by

the French priest, poet, and philosopher Félicité de Lamennais. Liszt made use of

only the first three and the longer final stanza of this eight-stanza prose-poem.

Rather than prefixing the words to the score in the customary manner, however,

he entered them directly into the score above the music, thereby making it

patently clear just how closely his music relates to the poem. Nonetheless, all the

evidence suggests that he never intended the piece to be performed with the

words declaimed simultaneously in the manner of a melodrama. Only fragments

of Lamennais’ text in Latin translation are sung by a male choir, which was not

added until 1866. The choir sings Beati mortui qui in Domino moriuntur at the end

of each stanza as well as the dialogue from the final stanza, De profundis clamavi or

Te Deum laudamus. Structurally, the addition of the choir further underscores

what was already true of the purely instrumental version – namely, that the music

is very closely aligned on the text. The four stanzas, with their textually identical

conclusions, are faithfully reflected in the music and merely flanked by a few bars

of introduction and conclusion at the beginning and end of the piece. At the same

time, however, they evolve from a process of variation to one resembling thematic

development. If the second stanza is an overt variation of the first, the relation

between the second and third is limited to the incisive principal rhythm. The

fourth stanza opens with a genuine passage of development that leads to a climax

beginning in m. 100.

The second ode, La notte, was composed from 1863 to 1866. As mentioned

above, it is based on a piano piece from the Années de pèlerinage, namely, on Il

Pensieroso, whose dirge-like rhythms make it the darkest piece in the Italian cycle.

The title refers to the like-named statue of Lorenzo de’ Medici that Michelangelo

created for his tomb in the Medici Chapel in Florence. At the same time, however,

the score is also preceded by a quatrain by Michelangelo himself that relates not to

Il Pensieroso, but to a different statue in the Medici Chapel: the image of a sleeping

woman, the Allegory of the Night (La Notte), from a group of sculptures on the

tomb of Giuliano de’ Medici. The same poem is also prefixed to the score of La

notte, but in this case the connection is made explicit by the title of the sculpture,

La Notte. In La notte the dirge-like gesture of Il Pensieroso is elaborated into a

complete stylized funeral march. A brief introduction is followed by a virtually

complete orchestrated version of the piano piece that largely adheres to the

original. A newly composed transition leads to a completely new central section in

A major noteworthy for its striking Magyarisms, especially the “Hungarian”

cadences. The piece ends with a varied recapitulation of the A section.

The relation between the third ode, Le triomphe funèbre du Tasse, and the

symphonic poem to which it forms an epilogue is much less rigorous. The only

musical link is the opening four bars of the Tasso theme from the symphonic

poem, which is quoted verbatim in mm. 92-95 and included with slight variations

elsewhere. The program underlying the symphonic poem is summarized in Liszt’s

preface as “the great antithesis of the genius, unrecognized in Life, but bathed in a

radiant nimbus in Death.” Thus the narrative impetus, which is projected in Tasso

using an ingenious fusion of single-movement sonata-allegro form and four-

movement sonata cycle, is the typically nineteenth-century passage per aspera ad

astra – from darkness to light. Being an epilogue, Le triomphe funèbre du Tasse

comes, one might say, after the story of the symphonic poem is over. Consequently

it does not outline a narrative trajectory: themes and motifs evoking lamentation,

triumph, and solace stand side by side throughout the piece. An introduction with

a chromatic motif (mm. 1-20) is followed by the presentation of three themes or

motivic groups: a triumphant variant of the Tasso theme in D-flat major (mm. 21-

40), a contrasting theme of distinctive lyric urgency in A major (mm. 41-69), and a

succession of motifs signifying lamentation (mm. 70-91). A reappearance of the

Tasso theme, this time sotto voce in E minor (mm. 92-107), is followed by a

melodious central section (mm. 108-139) that modulates from E-flat major via G

minor and A major to a triumphant transformation of the second theme in F major

(mm. 140-68). This transformation is in turn followed by a recapitulation of the

Tasso theme in A-flat major (mm. 169-91) and by the motifs of lamentation (mm.

192-206). A brief transition leads to a coda (mm. 212-45) that is especially

remarkable for its opening harmonies as F-major, A-major and D-major triads

alternate above an F tonic pedal in the bass that is garlanded with chromatic

neighbor-notes at one-measure intervals.

Steven Vande Moortele